Team health checks are a quick and high level way to assess how a team is feeling and doing. If you have never participated in one, imagine it as a quick survey along one or more set criteria, repeated over time.

I generally consider team health checks a form of baseline feedback: it’s something that measures quickly a state of a team in order to know if all the basics are in order. If they are not, then work needs to be done to reach a stable level, and if instead all is good then the team can start to stretch, grow, and expand their reach.

The repetition over time for me is where health checks shine as they are able to show changes in the team that might not have been surfaced otherwise, and to track progression and effectiveness of the work done.

Another great aspect of health checks is how flexible they are: they can be run synchronously (i.e. in a quick workshop), fully asynchronously (i.e. survey, recap, conversation), or mixed (i.e. survey, then workshop with results).

A general approach to team health checks

There are various kinds of health checks, but here specifically I’ll be focusing on the ones run at a team level, asynchronously. In terms of which questions to ask, these are the criteria I usually would advise to follow:

- Closed — A set of closed questions, to make the survey quick to fill out.

- Traffic Lights — Use red 🔴 / yellow 🟡 / green 🟢 scores in these questions, to avoid the illusion of precision and the frustration of trying to distinguish a 4 from a 5.

- Open — Have 1-2 open comment fields (could be more but not too many, the goal is to be quick), to allow people to integrate their answers with more details.

The questions should be designed to be stable over time: your aim is to have the same set of questions for a while, to allow measuring a change in scores properly. This doesn’t mean that all the questions need to be always the same. For example it could be useful to have some that change with the yearly change in the company strategy, to make sure the team is aligned. But if there’s a change, there should be always a set of questions that are fixed to maintain continuity.

In terms of how often the health check should be run, the answer comes from the team capacity to change and thus to influence the score. For the kind of questions I personally tend to ask, I believe that once every three months (every quarter) is long enough to register change, but also short enough to allow for adjustments.

The Person/Team/Product model

I want to outline a model I’ve used in recent years with good success when leading product teams. Most of the criteria are not contextual and will translate well in many different places — maybe with some tweaks. The reason why I’m fairly confident in this structure is that it provides multiple axis of analysis, it’s based on some fairly universal principles, and most importantly in my experience it correlated with my subjective day-to-day experience of a healthy team.

There are three groups of questions:

- Person

- Team

- Product

The person questions are meant to check the wellbeing of the individual. They are based on some key principles, they check for psychological safety, and they assess good mental health.

- Expectations: I know what’s expected from me at work

- Agency: I feel I can take decisions and move forward

- Effectiveness: I feel I’m delivering value to our users

- Safe: I feel safe in sharing my thoughts

- Growth: I feel I’m learning and growing

- Lead: I feel cared for by the team lead

The team questions try to evaluate the inter-personal relations between people, mostly within the group.

- Listened: I feel listened in our team

- Teamwork: I feel supported by my teammates

- Feedback: I receive solid feedback from my team

- Speed: the team works at a good speed, no delays

- Fun: it’s a pleasure to work with the team

- External Collaboration: we communicate well on projects with others

The product questions are more tied to the company as a whole, and the goal of the service we are working on. These might need to be made contextual to your product and organization, but they are regardless a good starting point.

- Focus: the vision of the product I’m working on is clear

- Roadmap: there’s a clear roadmap for our product to succeed

- Value: our product is delivering value to our users

- User Centric: we focus on the users first

- Processes: workflows are understandable and shared

- Quality: our product is well built

As mentioned, for each of these questions one can reply with one of the colors: red, yellow, and green. The results are then aggregated.

Analyze the results

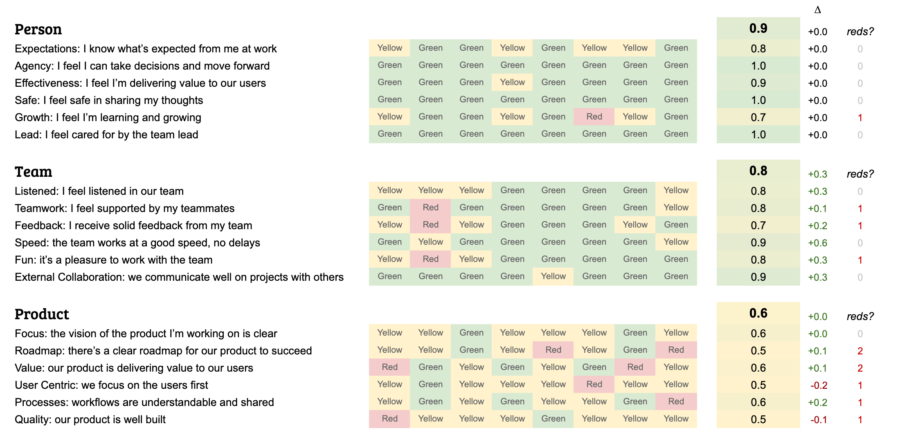

When working asynchronously we can review the results in more detail. There are three different layers of analysis of these results:

- Total score in each group of questions

- Heatmap of all results

- Reds for each question

- Comparison with the past

The total score is useful to have a high level index. The way I calculate it is simply to take each color, assign points to it, and then calculate the average rounded up to the nearest decimal:

- 🔴 Red = 0.0

- 🟡 Yellow = 0.5

- 🟢 Green = 1.0

Over time I tried to use % values, or out of 10, but after some adjustments I ended up with this range from 0.0 to 1.0. This is again because it’s important to be granular enough without however creating the illusion of precision: a scale having 10 steps (in 0.1 increments) is enough, and a maximum of 1.0 feels like something complete and less of some kind of high score to beat.

The heatmap is very useful to get an at-a-glance feeling of the results. It shows all the colors from everyone, for each question, anonymized. This visualization is incredibly valuable because it makes immediately evident both the overall status, as well as if there are low scores in one specific answer or with one specific person. It also makes evident some scenarios that scores won’t communicate well: a total of 0.5 might be the results of all yellow answers, or a mix of greens and reds. These are two very different situations to address: one is an average situation well spread across the team, the other is a mix of disjointed perceptions.

The reds are also something I count individually: even with a really high score, it’s important for me to make sure there are no reds. Reaching 0.9 but having 1+ red has a different level of urgency compared to a 0.9 with no reds.

Evolution of the results

Once the analysis of the latest health check is done, then it’s time to see what changed from the previous one. I usually review by comparing:

- Overall score and trends

- Overall ‘reds’ and trends

- The actions taken from the previous one

- Anything that happened in between

This comparison provides a lot of details to then assess if the work done was effective, possible hypotheses on the changes in the current one, and any possible next action that should be taken.

When I write the recap, this is the structure I use:

- Overall summary — this provides the high level overview with short bullet points

- Context — this outlines things that happened since the last health check that provide background to the results

- Changes from the previous one — this is a bullet list outlining what happened to the actions taken in the previous ones

- Personal — personal scores and comparison

- Team — team scores and comparison

- Product — product scores and comparison

- Quotes — direct quotes, anonymized, from the open questions

- Discussion — points that the team should discuss together

Anonymous or not?

Wherever possible, my suggestion is to follow this approach:

- the answers are personal

- the results are anonymous

This is because as a team lead I want to be able to reach out to individuals and ask questions, open discussions, and make sure people are listened to — and actions are taken, especially if there are reds.

However, outside the personal relationship, I don’t want anyone to be specifically discussed during a health check, and that’s why I completely anonymize the results. Any discussion should be about the team and addressed as a team.

If you feel the team isn’t “there” yet in terms of trust and internal culture to allow for non-anonymous feedback, it’s of course reasonable to keep everything fully anonymous: while this will limit the amount of direct support you can provide, the health check itself will give you a chance to prove that you are able to handle with care even difficult topics and act on them. This will build trust and could lead later to de-anonymize it.

Sharing the results

If working asynchronously, the analysis will then be shared with the team in textual form. This could happen via an internal doc, by posting on any internal team communication channel, or if the company still relies on email, via email. It’s ideal that wherever shared, there’s space for discussion.

If working partially asynchronously, or if there’s some hot topic to discuss, might be relevant to post the results — to allow for reflection time — and then have a small workshop to discuss the results and decide on next actions.

If the entire health check is done in a workshop, then just make sure the results and next actions are shared in some form, even if everything has been already discussed, in order to have a record to compare the next time.

Next Actions

If the team has already other sources of change and experimentation, like ongoing retrospectives, then there’s usually no need to add more actions from team health check unless something that was unseen elsewhere emerges.

However, if the team doesn’t have other activities that can lead to changes in these scores, or if there are some issues that need to be addressed specifically, then it’s important to follow up every result with a series of actions — and who owns these tasks.

While some of the actions are directly actionable by the team, others might not be fixable within. In this case it’s the responsibility of the lead to reach out and discuss what could be done with other leads, the boss, or other parts of the organization. It’s important to be explicit here because these two different set of actions should have different expectations — changes from the organization at large are usually more complex and slower than changes within the team.

Team health check results shouldn’t be read too strictly. While the numeric value can go up and down a little, there’s a lot of variability in people’s answers — might just have been something the day it was done, or something in the last couple of weeks. The importance of health checks is to create a track record and another open communication channel to allow change to happen.

What about objectiveness? These are subjective questions: team health checks are not performance reviews, research, or a way to get a universal score. They assess the team health, as humans and professionals, among themselves. By having top scores it doesn’t mean the team is the most perfect team ever, but what subjectively matters the most: the individuals in the team are healthy, the team is healthy, they work well together, they feel aligned with the organization. I usually consider an overall “green” score as the moment where the baseline is reached, and then the team can be pushed to grow to new heights. This push process might mean a temporary worsening of scores, and that’s ok!

Further readings

- H. Kniberg (2014) Spotify’s Squad Health Check model

- J. Rozovsky (2015) The five keys to a successful Google team

- Atlassian (2018) Health check for project teams