Competent people feel they don’t really know what they’re doing, and are just waiting for the other shoe to drop, for someone to expose them as a fraud. This is a fairly common phenomenon, with more than 70 percent of the population experiencing it at one time or another. Interestingly, impostor syndrome is worst among high performers. When I speak about it at Harvard, Yale, Stanford and MIT, I see the students breathe a sigh of relief as they realize this feeling has a name and they are not alone in experiencing it.

— Olivia Fox Cabane (Forbes)

Individuals with the Impostor Phenomenon experience intense feelings that their achievements are undeserved and worry that they are likely to be exposed as a fraud.

— J. Sakulku, J. Alexander (2011) The Impostor Phenomenon (PDF)

A phenomenon described in detail since 1985, I found the impostor syndrome useful to understand certain behaviours, relate better with people and situations, and be explicitly supporting everyone that is affected by it. I found out it’s a great notion to make the whole team aware because removes one layer of fears between the people, sending the message that’s ok feeling that way. For many people it’s relatable, and when expressed creates a safe space for it to be addressed.

How to identify the impostor syndrome

The term impostor syndrome has however been diluted over time. The lighter, popular version it’s usually defined as a higher than average feeling of inadequacy. While this can surely be a problem, I believe it’s important to identify the impostor syndrome more tightly going back to the original definition. What are the criteria we can use?

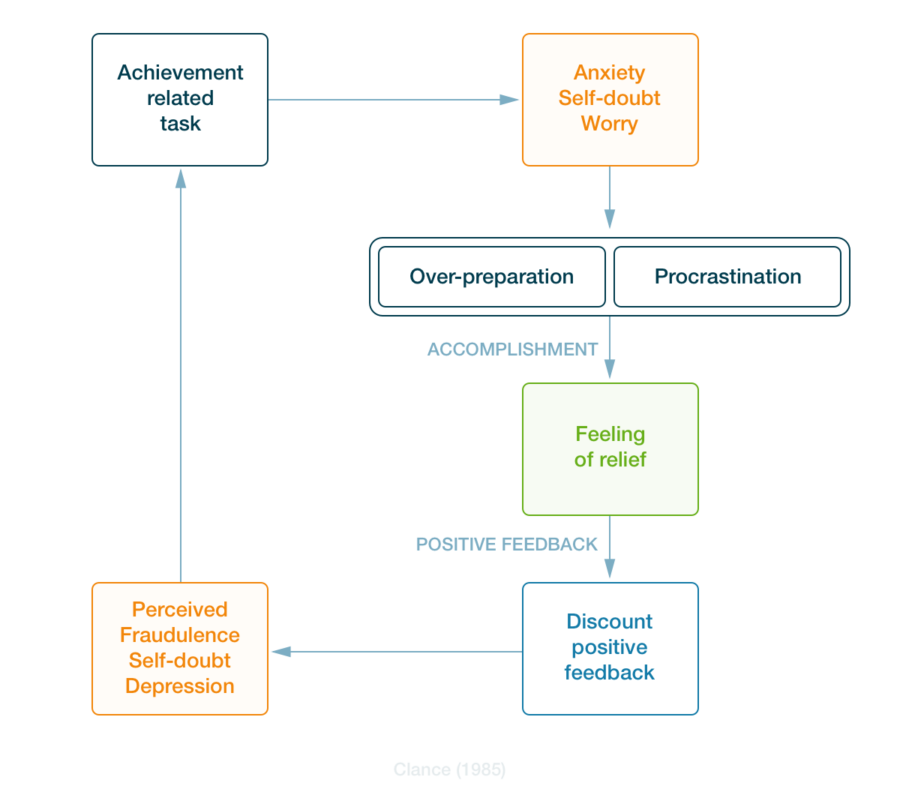

This diagram from Pauline Rose Clance (1985) is a good reference:

In the paper these points are used to define the impostor syndrome:

- Cycle of task → anxiety → perfectionism → relief → discount.

- Overworking.

- The need to be the very best, to be special.

- Superwoman/superman ability to perform flawlessly.

- Fear of failure.

- Denial of competence.

- Discounting praise.

- Guilt about success.

People with the impostor syndrome often have strong beliefs that they will become a failure if they do not follow the same working style.

I personally use these simplified criteria:

- Success is discounted: the person isn’t able to feel the impact of success and quickly moves to the next problem to solve, the next achievement, the next confirmation.

- Over-preparation driven by self-doubt: the person usually has a higher than average level of self-criticism that raises the bar for what they are trying to achieve. This self-criticism sometimes becomes also criticism oriented outward, but it’s not always the case.

- Constant need for achievement: due to the short lived relief and success being discounted, the person needs to keep achieving in order to maintain an adeguate level of self-worth.

- It’s a cycle: even if logically being able to achieve success should be able to break the cycle, in practice this doesn’t happen. No achievement is ever enough for the person to feel a sense of self-worth. Thus, the cycle keeps perpetuating.

This also means that the individual objective ability to do things is never properly assessed, but always conditioned by the subjective perspective of lack of self worth.

For people with impostor syndrome,

success does not mean happiness.

These criteria should help you both in your self reflection and in recognizing it in other people. If you think you have it, my advice is to work on the lack of self-worth, specifically by getting some kind of therapy — which in my opinion it’s something that everyone should be doing regardless.

Helping someone with impostor syndrome

What if someone you work with has the impostor syndrome? In general I think we can’t do much for them as it’s something they have to work on with themselves. However, there are things that can be done to help at work:

- Help them ground their work by confirming good outcomes, adding details as precise as possible on why you think the work was good.

- Provide periodic assessment of the work done so far, helping them to gain perspective of the achievements reached.

- Keep a list of their achievements for them.

- Give them criticism. This might sound counter-intuitive, but being able to give people something to work on about themselves and fix it doesn’t just give another achievement to feel good about, but also makes your positive words more sincere: “oh they don’t just say that to make me feel good”.

- Normalize the feeling if possible, share your own feelings of inadequacy. Even if you don’t have the impostor syndrome, you might feel inadeguate from time to time or you might feel some tasks hard. Sharing these help the person to feel less alone.

Note that the above does not resolve the impostor syndrome — that requires therapy, which I’d advise to everyone regardless — but it’s something that people without expertise in psychology can apply in the day to day.

I hope the above are a good starting point for you. If you have more techniques that you feel work, let me know.