We are having an hard time in even defining what a single company culture is, no wonder we have problems when there are mergers:

Approximately 70% of mergers and acquisitions fail to achieve expectations and 50% destroy value.

— VSC Growth (2011) M&A Research Report

How can we merge something most of the time we fail to acknowledge?

The reasoning of mergers, even if good-intentioned ones (i.e. not driven by purely financial or stock reasons), is that we expect that two things that work well independently will work well together as well, taking a purely mechanical viewpoint that fail to acknowledge basic human psychology.

Still, as the are ways to build and frame properly a company culture, there are similar ways to merge two company cultures.

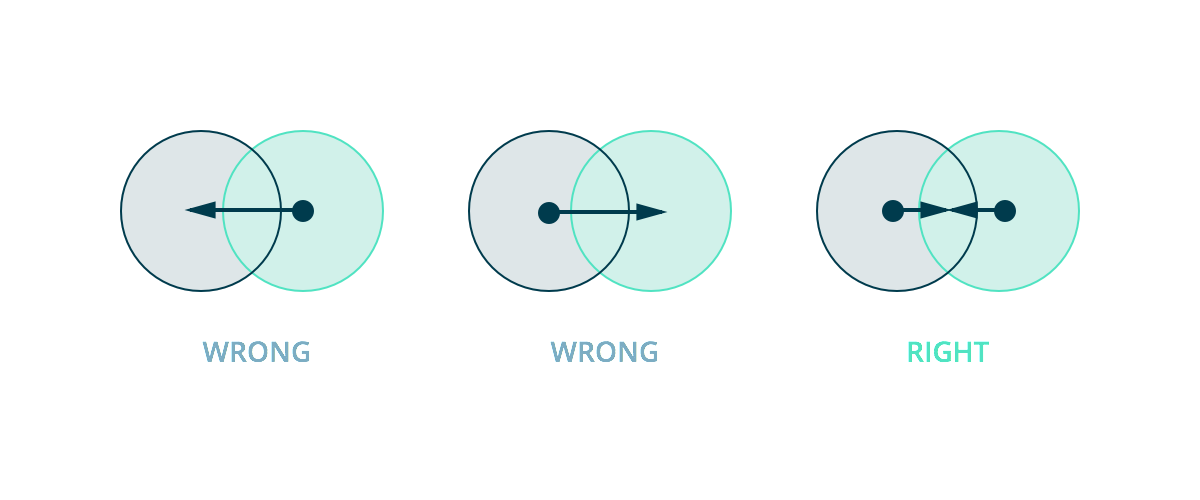

This has to start with the acknowledgement of the two cultures and identify the aspects that inevitably will:

- be identical or convergent, in order to create a positive push toward a common, shared ground.

- be different or divergent, in order to account for the differences and take the best out of them, without creating a direct push against them which will estrange one of the two groups.

The intent is to find the common ground, without crushing any of the two cultures. This of course will be tuned differently in terms of the different relative sizes of the companies and kinds of culture, but overall, has to be part of the acquisition process.

A recent HBR article, Merging Two Global Company Cultures, points out four factors:

- Decategorize — break the perception that the “other” group is a single entity, and make people know other people. The intent is to reduce the stereotypization of the other group.

- Recategorize — create a higher-level category that include both groups, to create a new sense of “we” that respect both sides.

- Mutual differentiation — identify the parts that are different but complementary, and create ways for them to work together.

- Healthy debate — conflict, in one form or another, will happen, so making the dialogue open and creating avenues for people to express is important, as a way to understand and address the concerns.

The final, but not less important bit in this context is to acknowledge from the onset that something will be lost for sure. Setting the expectations of 100% results is plainly impossible, even if sometimes from some specific metric this results will be achieved, won’t be as a whole.

So for example, you have to consider that some people will leave, and that’s perfectly fine and not a sign of failure by itself (this even not including the problem of “duplicated management roles, i.e. having two VP of Marketing).

And a bad way to deal with this is this one:

Finally, alienation is the degree to which employees who don’t fit in come to leave of their own volition. Either peers or management could ignore the employee in question, or give him or her difficult or unpleasant assignments until the employee simply quits.

— Alice LaPlante (2006) Glenn Carroll: How Do You Successfully Merge Two Corporate Cultures?

Alienating someone to make the individual leave is just terrible advice, and it’s eve worse because in this case they are advising to do this on purpose instead than talking with the person and finding a solution together.

Which means that acknowledging these things is just a first step: then you need to find the proper way to move forward.