Nemawashi is a semi-formal but systematic and sequential consensus building procedure in Japan by which the approval of a proposed idea or project is sought from every person in a significant organizational position.

M. Fetters (1995) Nemawashi essential for conducting research in Japan

With the premise that I haven’t worked in a Japanese organization directly, so I can’t speak to the practice as semi-formally used in the Japanese culture, I think the word and its definition fits an important skill that anyone should learn and improve — I believe it’s one of the most important skills on the workplace (and useful even beyond that).

Coaching, affiliative, democratic, commanding, pacesetting, visionary: four out of six leadership styles are grounded in nemawashi, unsurprisingly all the ones that are related with a positive climate.

Why nemawashi works

Let’s say there’s an idea we want to push forward. By going for a common western knowledge, we just need to make sure it’s a solid idea, propose to our boss (or someone in power) and if the idea is good enough, it will be chosen. While this is true, it’s also part of the sole genius myth, and the usual myth that ideas gets chosen by merit alone.

But wait: how can it be a myth, if we see it working so often? Even if we ignore for a moment the obvious fact that many ideas get rejected, it’s because we ignore the ecosystem where this myth lives. One common scenario is that we have already built trust with both our boss and our colleagues and we might have also informally discussed this ideas for weeks or months. Another scenario is that the boss, or someone in power, is putting in effort for us. Another one is… just luck.

As you can see, if we want to rule out luck, there’s a lot of work put into the context around the idea pushed forward: that’s what nemawashi makes explicit.

Let’s rewind, and go back to the idea we want to push forward, this time using a nemawashi practice. We are going to prepare a draft, as we did before, but this time we check in with colleagues and bosses, to build consensus. Once everyone, including our manager, agrees, then we can make it happen.

What nemawashi effectively changes is:

- It reduces the risk of the idea by involving key people, and importantly key expertise, in the process of making it real.

- It reduces the time required, because moving all the consensus building work from after to before, it means that conflict is avoided and thus time is saved.

- It increases people involvement in the idea, because their feedback is now part of it and it has contributed in making it better.

- It increases the likelihood of success, because the idea is refined by the perspective of many people before it gets pushed forward.

Counter-intuitively, the time is effectively reduced, not increased. I think everyone has experienced directly or indirectly someone resisting an idea just because “they weren’t asked”, or some change that would have made the idea so much better yet it came late so it required to re-do a lot of work.

Make decisions slowly, execute them quickly.

Without nemawashi, this is just hidden cost. Which is why the commanding leadership style, being the exact opposite of nemawashi by just giving orders, has a high cost in terms of team health and work climate. The speed a team acquires in the short term is going to be paid a few weeks later. That’s one of the reasons why the commanding style should be adopted only for short term activities or emergencies.

Note: nemawashi is also helpful in removing meetings, as a large number of these exist to discuss, review, and evaluate a new ideas, and they are thus replaced by just one short meeting to approve it, and a lot of smaller interactions before it.

How to do nemawashi

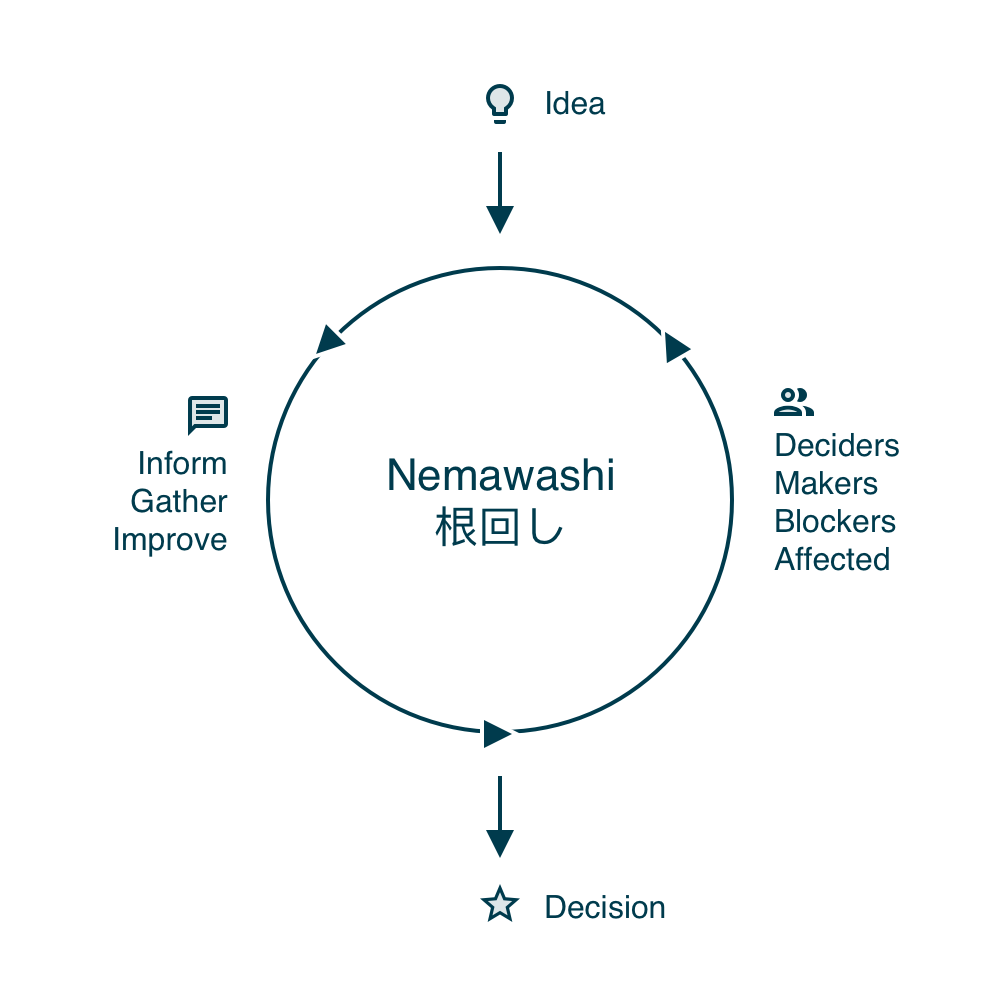

We can define nemawashi as composed by a few different elements:

- Idea draft: concept, problem, why

- Key people: deciders, makers, blockers, affected

- Consensus building: inform, gather, improve

- Decision making

The idea starts being shaped by the individual or group of individuals that had it. This is nothing new, and should include a clear explanation of what the concept is, what problem does it solve, and why it’s a good idea to pursue. Think of this as the first working draft.

Then prepare a list of key people that are important to involve in this idea. We need to include decision makers and in general people that have power, as they are the ones ultimately deciding for it. We then need to identify the experts that will work once the idea gets moved forward. Depending on the company culture, you might also need to identify more explicitly potential people that might end up blocking the idea, for one reason or another. While I hope this list is empty in your group, sometimes it just helps to be prepared. Finally, there’s a likely larger group of people that will be affected by the idea, either directly or indirectly. These people are also very important as they might provide a unique perspective.

Then we start talking with all the people on this list. The order can vary, and depends a lot on the idea, how it affects people, its size, and so on. Sometimes it might make sense to start with the most key person on the list, sometimes it might be better to start with some of the most expert ones in order to make the idea more solid first.

Notice that nemawashi can be very open and transparent. In the most open form, it becomes akin to community management: all on the open, all visible. Most of the time, it’s a mix of some informal private discussion and open ones. The balance depends on the culture.

We are informing people about it, gathering their feedback, with the goal of making the idea better for everyone. We aren’t trying to make people change their mind forcibly. We are aiming to get people part of the idea by contributing their own bit, or, if the idea in the end is not great, to get it criticized early so we don’t spend too much time on it. We are building consensus openly, not forcing consensus.

One technique that I can advise and that works well is to do some preparation before speaking with someone and connect the new idea with something they have suggested themselves, or something they find positive. It can make a big difference to start a discussion with “The other week you said this, so I think that this idea is aligned with what you were saying” compared to “Here’s a new idea I just had”, which is likely to make them think “Wait, that’s what I said the other week? That’s not a new idea at all!”. And of course, remember to always give credit.

Especially for people that are likely to block the idea, but in general for anyone that might get negatively affected, it’s often possible to work with them to figure out a way that might make the problem go away entirely, or at least be minimized. We need to be attentive, listen their concerns, and take time to find a solution.

At the end of the consensus building part we will find out that either the idea wasn’t as good as we thought it would be (that’s ok! let’s move on and find a new idea!) or that the idea is now way stronger than when it started out. And even if there was almost no change, everyone now is ok with it, and we know we can move forward effectively.

Finally, we reach decision time, the moment when the idea can be put on the table, and made it happen. As this was already discussed extensively, this moment is usually short, and without any surprise.

How it can go wrong

Nemawashi is not groupthink or design by committee. The approach needs to be used to reinforce and improve the idea, not to dilute and twist it. We need to be careful in balancing the incorporation of expertise and opinions that make the idea better, with incorporation of opinions just to get the people on our side.

Nemawashi is also not about hiding things or working behind the scenes in private. If anything, it needs to be a process as transparent as possible. In some cultures nemawashi can be done more privately to avoid people “losing face”, but otherwise, it should be an open process.

This is something that is up to us to learn, and it’s one of the hardest things to do well. Sometimes it’s important to not change the idea just to get someone onboard, which requires to go a little deeper in the discussion and highlight the reasoning. Sometimes it’s instead ok to incorporate a change even if we think it makes the idea a little less strong just because it’s the difference between getting the idea going, and not doing it at all. It takes a lot of experience to find this balance, and never compromise the “core” of the idea at early stages.

It’s also important to avoid making this process too formal. We need to get the fundamentals, use the outline above to see where we can improve, yet we must avoid making it a stiff step by step sequence of steps. We can use the benefits above to review if the way you’re using nemawashi is solid:

- Is it reducing risks?

- Is it reducing overall time?

- Is it increasing people involvement?

- Is it increasing the likelihood of success?

Q&A

Isn’t this just normal between people in a healthy environment?

In many ways, yes. But if we want to improve, it’s important to define what we are trying to get better at. It’s also even more relevant if we work with people or in a group where this doesn’t happen, as it will contribute to make the group healthier.

Doesn’t this mean that every small decision now requires weeks?

No. Not everything needs to be done at a large scale. A small decision might just require five minutes to clarify our mind on what, the problem, and why of an idea, and a five minute chat with one person. Also, the better we get at this, the more natural it will become and part of our day-to-day.

Isn’t this a lot about politics and lobbying?

As it happens with many ideas, it can be twisted in many bad ways. So yes, taken badly the same practices can be used to create pressure, thwart ideas, and slow down work. The difference as usual is about intent, and to be always on alert to make sure the negatives don’t creep in.

Is is this sufficient to take good decisions?

No. This is about group dynamics and decision making, not about the goodness of the idea on its own. It’s like describing how good book editing should happen: editing is crucial, yet someone has to write a good book draft in the first place. Also, a great idea might just not be a good fit for a specific company, that’s ok, it doesn’t mean it’s bad.

Does this work in communities and flat organizations?

Yes. While the use of the word is in many ways business-centric, nemawashi even more important for decisions in open-source communities and in general any flat organization structure. This is particularly evident when people that are used to decisions-by-hierarchy try to get into communities: they apply their usual approach and they crash. Nemawashi instead works in both scenarios. This is often why people that are able to work in communities are usually way better at managing people: they learned in “hard mode”.

Related Readings

- Wikipedia Nemawashi

- Dr. S. Sagi (2015) “Nemawashi” A Technique to Gain Consensus in Japanese Management Systems: An Overview

- R. Kropp (2012) Defining Nemawashi

- A. Smalley (2012) Nemawashi in Toyota

- Reinventing Organizations (Teal Orgs): Decision Making (Advice Process)

Note: this draft took me a long time because I was very wary in borrowing a Japanese word while I haven’t directly worked in that culture. Still, the first time I read about it, the concept resonated. I tried to read about it as much as I could, especially in the original Toyota formulation, to avoid misinterpreting the concept, and I’ve asked Japanese people and people that know Japanese culture if my interpretation was correct. The answer I got was overall positive, so I eventually decided to go forward with it.